Part I: The Child Archetype and the Creative Process

Anakin, as a literal child in The Phantom Menace, personifies the child archetype. After reflecting on the meaning of Anakin’s role as the child, I combined my findings with the advice of a practicing artist. As a result, I developed a better understanding of the obstacles that creative people encounter when engaging in a creative process. By acting on that understanding I was able to overcome the obstacle that I have struggled with the most throughout my own creative endeavours.

Much of what I have learned about the child archetype is drawn from Carl Jung’s paper, “The Psychology of the Child Archetype.” To sum up, the child archetype is a symbol for that which unifies the conscious and unconscious halves of the human personality into a whole (1). The important take away from this summary is that the whole personality is like the adult that the child is going to become. However, this whole personality is a paradox because it is an adult with a child-like quality.

The child’s journey towards wholeness is an apt analogy for any creative process because the child’s journey is a creative process, albeit a creative process of a psychological kind. Although, to be honest, any creative process that the human being engages in is psychological, at least in part, and not just physical. Whether you are creating something with materials, such as a painting, or creating something more abstract, like a new identity for yourself, you are engaging in a creative process that is psychological in nature. The child, by uniting the opposite halves of the personality, is creating something seemingly abstract, that is, the aforementioned state of wholeness.

Part II: The Child and The Setting of Star Wars

Anakin’s purpose in the Star Wars narrative is to bring balance to The Force, which is made up of the opposites of light and dark. Bringing balance between the light and the dark is just another way of expressing the unification of the conscious and unconscious halves of the personality. The Force is in a state of imbalance or disunity, which bleeds into the galaxy’s political situation. According to Senator Palpatine, “the Republic is not what it once was. The Senate is full of greedy, squabbling delegates. There is no interest in the common good.” Palpatine’s exposition describes a society with a consciousness that is clouded by fear and greed, by the dark side.

The states of disunity and unity have their counterparts in the Grail motifs of enchantment and disenchantment. Anakin’s job is to disenchant, through his compassionate acts, a galaxy that has been enchanted by fear and greed. As the Prequel Trilogy progresses, Anakin becomes enchanted by fear and greed, and in consequence, loses touch with the compassionate child he once was. As Joseph Campbell once wrote about the Grail heroes Parzival and Gawain, Anakin too, “must disenchant himself before he is able to disenchant the Waste Land” (2). To disenchant is to create a state of wholeness, a personality and society with a consciousness unclouded by fear and greed.

Part III: The Child and The Boxes of the Mind

Years ago I listened to an interview or a commentary with Star Wars director George Lucas, in which he describes, in his own terms, what sounds like the motifs of enchantment and disenchantment. I was unable to track down the source for Lucas’ observations in preparation for this blog post. To summarize from memory, Lucas explained that his movies are about people trying to escape from “the boxes of the mind.” These boxes are the enchantments that must be dispelled. An example would be the emotion-suppressing drugs in Lucas’ first feature, THX-1138. In Star Wars, the primary boxes are the previously mentioned diabolic twins called fear and greed.

Lucas does not refer specifically to the child archetype when discussing the boxes of the mind, but I would argue that Lucas’ characters are actually trying to free the child in themselves—the symbol for that which creates wholeness—from the boxes or enchantments that prevent the child from completing its creative process.

The boxes of the mind motif is not only present in Lucas’ movies, but in his creative process as well. At Star Wars Celebration 2017, Dave Filoni, Supervising Director of Star Wars: The Clone Wars, shared what he learned about creativity from George Lucas:

When you’re coming on board to like, direct this major franchise that all of you love and around the world people love, it is easy to get overwhelmed by that and that idea. And that is going to limit you and more importantly limit your creativity if you become afraid of it. So, you can never be afraid of things, to try things, to experiment…To do things that have never been done. When we would find something that a lot of people would say, “Well, you can’t do that”…It’s the first thing George would say, “Okay, we’re going to do that” (3).

The fear and naysaying that Filoni describes above are boxes that stifle the child and its creative process, boxes that, according to Lucas are not to be tolerated. Having to deal with fear makes it obvious why any creative process undertaken by a human being is psychological in nature, because dealing with fear, a regular companion to creativity, is a form of psychological labour.

Part IV: The Creative Person’s Relationship with the Child

The idea of labour leads us to discover what kind of relationship a creative person has to that which they are trying to create, or more precisely, to that which is trying to realize itself through them. Jung confesses in his Liber Novus that “the spirit of the depths teaches me that I am a servant, in fact, the servant of a child: This dictum was repugnant to me and I hated it. But I had to recognize and accept that my soul is a child and that my God in my soul is a child” (4). Like Jung’s relationship with his soul, the relationship between the creative person and their creation is that of a parent to a child. Jung does not use the term parent, but the term “servant of a child” conjures the image of a parent in my mind because to be a parent is an act of service to a child, and this service, as any parent is likely to attest, is one of considerable labour. If the creative person attaches parental feelings to what he or she is trying to create, these feelings can provide the necessary energy for the labour needed to free the child from the boxes of the mind.

Part V: Overview of Anakin’s Child Characteristics

Using Anakin as an example, we’ll now examine some of the characteristics that he shares with the child archetype as detailed by Jung in his paper. These examples serve to illustrate the child’s struggle against the forces that try to box it in and how it is that the child manages to overcome them.

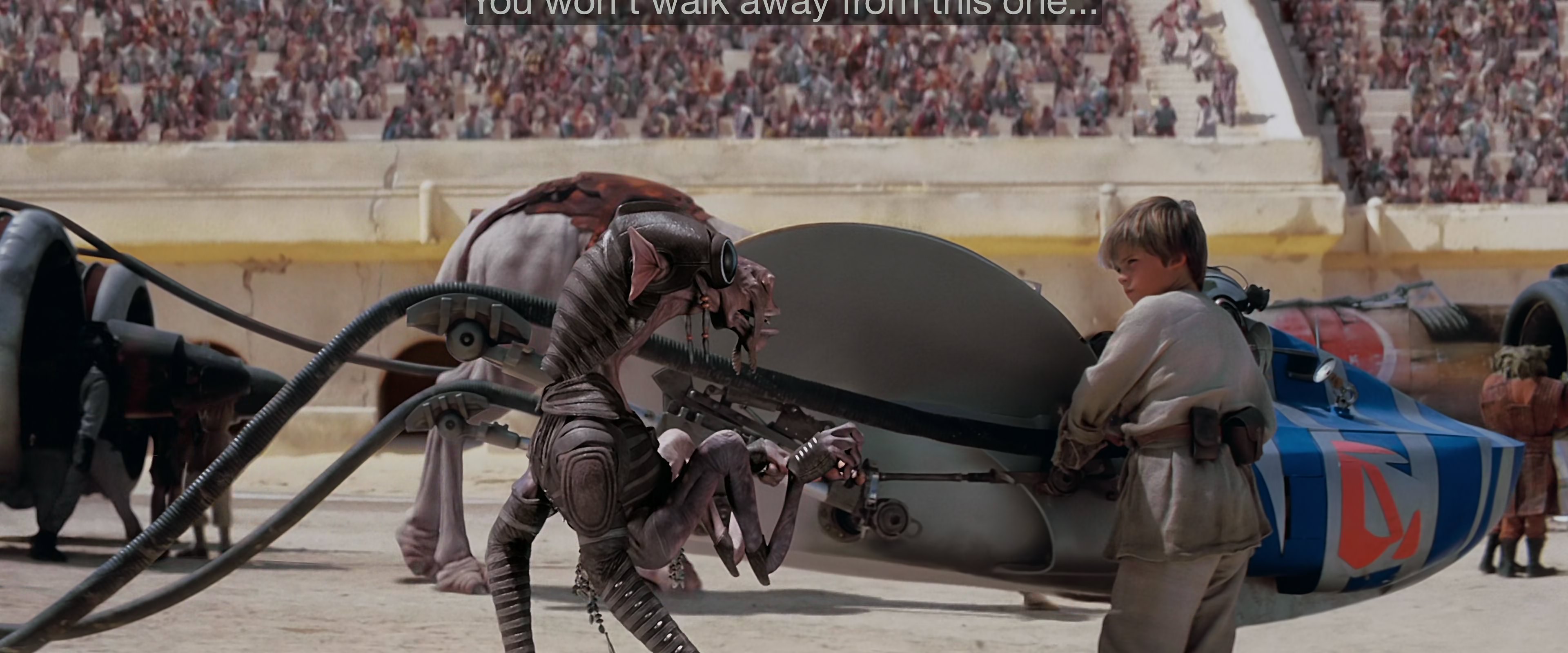

- The child is exposed and endangered (5): Every time Anakin participates in a podrace, his rival, Sebulba, tries to kill him via acts of sabotage. Over the course of the series, Anakin’s fear of loss exposes him to the dangers of the dark side of The Force.

- The child is in a state of abandonment (6): Anakin meets this characteristic because he is enslaved on a planet in the Outer Rim where the laws of the Republic do not apply, meaning that he is abandoned by the Republic. The fact that the Republic would abandon a compassionate child such as Anakin is evidence that the society has abandoned compassion itself in favour of greed.

- The child is insignificant (7): Anakin, as a slave, occupies the lowest social status possible. He is also insignificant in regards to podracing because he has never managed to finish a race. Therefore, he is not seen as the favourite to win the Boonta Eve Classic.

- Despite the above qualities, the child is divinely powerful (i.e. has powers beyond that of the average person) (8): Anakin is the only human that can podrace. Qui-Gon explains this phenomenon by saying of Anakin, “he has special powers. He can see things before they happen. That’s why he appears to have such quick reflexes. It’s a Jedi trait.”

- The child performs miraculous deeds (9): Anakin wins the podrace and even destroys the droid control ship by accident.

Jung discusses more traits in his paper than what I have listed above, but suffice to say, the above qualities give a broad impression of how Anakin manifests the traits of the child

Part VI: Endangerment, Exposure, Abandonment, and Insignificance

The purpose of the traits of insignificance, exposure, abandonment and danger is to communicate “how precarious is the psychic possibility of wholeness” (10). Like the child, all creative processes exist in a state of peril. In my experience, whenever I undertake any creative endeavour, it amazes me how swiftly the boxes of the mind swoop in to put an end to the process before it can reach its conclusion. Fear-driven naysaying, of the sort that Lucas and Filoni encountered, although, primarily from within, is for me the most prominent.

As mentioned above, Sebulba endangers Anakin via acts of sabotage, such as when he tampers with the engine on Anakin’s pod before the race. Even Sebulba’s dialogue is a form of sabotage. For example, he tries to intimidate Anakin before the podrace, telling the boy, “you won’t walk away from this one, you slave scum.” Therefore, Sebulba is the embodiment of fear-driven naysaying, that voice in every creative person’s mind that tries to sabotage everything they set out to create.

Luckily, Anakin has zero-tolerance for this kind of fear-driven naysaying, contradicting Sebulba’s verbal sabotage with, “Don’t count on it, slimo!” What this means is that Anakin is not enslaved by the fear that Sebulba deploys against him. Anakin’s inward situation is in contradistinction to his outward situation of enslavement. If Anakin allowed himself to be enslaved by the box of fear he would not win his outward freedom, and as a result, he would not complete his creative journey towards becoming the Jedi who can create a state of wholeness both within and without.

Like the child in its state of abandonment, the creative person can feel abandoned in the midst of their creative endeavours, especially at those times when they are besieged from all directions by the boxes of the mind. However, the creative person, and that which they are trying to create, or who they are trying to become, is only truly abandoned when the creative person believes their inner Sebulba when he leans over and whispers in his or her ear, “Well, you can’t do that.” It can be dangerously easy to believe Sebulba’s sales pitch. The reason for this is because, when a creative process begins, it often shows no clear signs of success. It appears to be, and may very well be insignificant. This is the equivalent situation to Anakin’s abysmal racing record. Therefore, serving the child is nothing less than an act of faith.

Part VII: The Child’s Divine Powers and Miraculous Deeds

To counter the forces of endangerment, abandonment, exposure, and insignificance, the child uses its divine powers. Jung explains that the child comes “equipped with all the powers of nature and instinct” (11). These are its divine powers. In fact, it is because the powers are of nature that they are divine. Anakin’s Jedi abilities are his most obvious divine power. After all, they are the very thing that makes Anakin capable of winning the race, which is one of his miraculous deeds. Before the race, Qui-Gon even advises Anakin to use his instincts, which one assumes is a set of instructions for accessing his Jedi abilities more reliably. As a result, no matter what Sebulba does during the race to endanger Anakin, Anakin escapes the danger by using his Jedi abilities.

Besides winning the race, Anakin’s other miraculous deed in The Phantom Menace is his accidental destruction of the droid control ship. The fact it is by accident is immensely interesting. Again, it is Anakin’s powers that allows for this to happen. The powers, being of nature, hints at the idea that it may actually be nature itself, The Force, acting through Anakin. Even when Anakin doesn’t intend to bring about a particular outcome, nature has other ideas. Remember, in A New Hope, when Luke asks Obi-Wan if The Force controls your actions, Obi-Wan answers: “Partially, but it also obeys your commands.”

Jung further reveals the power of the child when he describes the child as “the strongest, the most ineluctable urge in every being, namely the urge to realize itself. It is, as it were, an incarnation of the inability to do otherwise” (12). I can’t help but read Jung’s description and conclude that the child sounds awfully stubborn. If the child is equipped with the powers of nature and instinct then it stands to reason that stubbornness is one of these powers. Anakin’s intolerance for the boxes of the mind is a great example of his stubbornness because no matter what anyone does to deter him from participating in and winning the podrace, he just isn’t having it.

Creative people are well acquainted with the stubbornness of the child. When creative people neglect their craft for too long, the child has a way of correcting this behaviour. If you don’t help free the child from the boxes of the mind, or as Jung puts it, from a conscious mind “caught up in its supposed ability to do otherwise” (13), then the child, to put it mildly, is going to make the creative person an offer that he or she can’t refuse. This it accomplishes by rendering the creative person so miserable that he or she has no choice but to tend to the child.

The child’s stubbornness or resistance to limitations is paradoxical because it demonstrates the child’s flexibility. This, the child shares in common with the uncarved block of Daoism. The image of an uncarved block, itself, conjures the image of solidity. However, the uncarved block is the portal to flexibility. The uncarved block is what the Zen koan refers to when it instructs the listener to, “Show me your face before you were born.” To stay in the boxes of the mind is to retain one’s current face (the carved block), which for Anakin, would be his identity as a slave (an identity he never actually accepts). What Anakin, as the uncarved block, teaches humanity, is that we are capable of unbecoming who we are currently so that we can become someone new. To return to the uncarved block is to become open to possibility. Therefore, the child-like personality is defined by a growth mindset as opposed to a fixed mindset. In other words, Anakin, as the child, shows us that the human personality has the power to shapeshift. This is what Master Yoda meant when he told Luke to “unlearn what you have learned.”

Part VIII: Compassion and The Child

Above and beyond any of Anakin’s other powers is his ultimate divine power…The power of his compassion. After all, in stark contrast to Sebulba, who is destructive out of a greedy desire to ensure his own victory, Anakin’s creativity is driven by a sense of compassion. When he hears that his friends are stranded on Tatooine because their ship is damaged, Anakin manifests the creative energy that is contrary to the energy of the saboteur when he insists that he “can fix anything.” Instead of sabotaging other racers’ pods, Anakin builds his own and offers to race it to win the parts his friends need to repair their ship.

Over the years, Anakin becomes disconnected from the child that he once was, and thus, he loses his power of compassion. The motivation of his desire to fix anything becomes rooted in fear and greed instead of compassion. When he tries to save his wife, not to prevent her suffering, but to alleviate his own, the result is destructive instead of creative. His inner child is enchanted by the boxes of the mind and is prevented from completing its creative process. Of course, compassion is the power Anakin will one day need to disenchant a galaxy that has been enchanted by fear and greed. Due to the fact that compassion is the key to unlocking the boxes of fear and greed, it is indeed Anakin’s most divine power.

Anakin re-discovers his compassion or returns to the uncarved block when he witnesses his son suffering at the hands of the Emperor. At this moment, in contrast to his experience with his wife, Anakin wants nothing other than to end the suffering of someone other than himself. Anakin’s parental feelings for Luke reignite the compassionate energy necessary to overcome the enchantments of fear and greed that have enslaved him to the Emperor. In doing so, he can be of service not only to his literal child, but more importantly, to the child within as well. By serving the child, Anakin ensures the fruition of that which is trying to realize itself through him—a state of wholeness—the Force in balance. He throws down the Emperor, and in thus doing, disenchants the galaxy from the “spell” that the Emperor cast over it. The lesson here is that the creative person must have compassion for that which is being created through him or her above all else.

Note: The “servant of the child” motif reoccurs in Star Wars: The Mandalorian.

Note: The “servant of the child” motif reoccurs in Star Wars: The Mandalorian.

Part IX: My Escape From The Boxes of the Mind

By examining Anakin’s journey the crucial takeaway is that compassion is a necessity for the escape from the boxes of the mind. That’s all well and good, but what does this look like for the creative person in the real world? An episode from my own experience should provide an adequate illustration.

As I touched upon previously, the most common box, in my experience, is fear-driven naysaying. Whenever I create something, my inner Sebulba tags along, speaking to me in the language of fear, launching verbal sabotage such as: “you don’t have enough time to do that,” “it isn’t going to turn out well,” and “that’s going to be too stressful for you.” If I understand myself correctly, all of these fears are rooted in entitlement, a type of greed not entirely unlike Sebulba’s. You see, Sebulba doesn’t want to earn his victory, and whenever I create anything, there is a part of me that wants to achieve victory without any discomfort whatsoever. It would be easy to wallow in self-pity the moment one realizes that one’s fear is rooted in entitlement, but the trick to avoiding this self-pity is to recognize the utility of one’s fear and entitlement. While fear and entitlement are, indeed, the boxes that entrap the child, and compassion is the key that sets free the child, I learned from a practicing artist that the boxes don’t have to be entirely antagonistic to the child.

Here’s how it happened…In July 2019 I heard that my local college would be hosting a free three-day filmmaking workshop. I knew instantly that I wanted to attend, but predictably, Sebulba leaned over and whispered in my ear: “Making a film in only three days sounds really intense. You can’t handle it.” By this time in my life, I could recognize the voice of fear for what it is: a box in the mind. I knew that it was catastrophizing, exaggerating, and imagining worst-case scenarios. Adopting Anakin’s policy of intolerance towards Sebulba, I ignored the voice of fear and signed up for the workshop.

The day before the workshop I did my best to keep ignoring the voice of fear no matter how loud it became. Being intolerant of my fear is an approach that has worked for me before, but I was definitely wavering on whether or not to go through with the workshop. That day, I was listening to “Episode 40” of the podcast, Fun with Dumb, in which artist Lauren Tsai discussed her fears in regards to showing her art to an audience for the first time. What she had to say about her experience is: “if you’re scared of something, it’s because it matters to you. If you can tackle that, you really become stronger” (14). Let’s just say this piece of advice cut through my fear and entitlement with the precision of a lightsaber. At that point, I said to myself, “Okay that settles it. I have no excuses. I have to do this workshop because filmmaking definitely matters to me.”

Lauren’s approach is so effective because it transforms fear into a compass that points the way to what is of value to the person who feels the fear. In hindsight, I felt entitled to success because filmmaking matters to me. Thus, I was afraid of the potential for discomfort if I performed poorly at the workshop. However, that sense that something matters to you, is actually your feelings of compassion for that which is trying to realize itself through you. Lauren’s advice focused my attention on that compassion, which rendered fear and entitlement incapable of preventing me from serving my inner child. If Anakin’s compassion allowed him to suffer for the sake of his son, and in so doing, bring balance to The Force, then I, at the very least, could certainly withstand some discomfort for the sake of that which is trying to realize itself through me.

If we take a second, closer look at George Lucas’ approach to fear, even though he seems to regard it with intolerance, we can see that he too is actually using it as a compass. Remember, Filoni says that when he and George were bombarded with a fearful, “‘Well, you can’t do that,'” George would respond, “‘Okay, we’re going to do that.'” Even if the former phrase disgusts him, he is still using it to confirm valuable ideas. However, I failed to see his approach in this light until I considered Lauren’s point of view. Lauren showed me that creative people can regard fear and entitlement with gratitude instead of intolerance.

So, for all you creative folks out there, the next time your inner Sebulba tells you, “Well, you can’t do that,” you can respond: “Thank you Sebulba. Your attempts at obstruction have shown me that I am on the right path.”

And, for good measure, make sure to compliment Sebulba on his goggles. After all, he does have some serious goggle game!

Part X: Conclusion

While the child can be thought of as that which is trying to realize itself through the creative person, it is not just the end product of the process. Why is this? It is because “the child motif represents not only something that existed in the distant past but also something that exists now” (15), and furthermore, “the child is potential future” (16). To put it plainly, the child connects past, present, and future. It is the seed and the fully-blossomed tree. This is why Anakin’s compassionate behaviour as a child points to his future compassion in regards to his son and his compassion towards his son is rooted in the compassionate child he once was. The end product of a single creative act is merely one stage of a greater process, part of a greater whole, a whole that is the child itself. What this means for the creative person is that to be in service of the child is a lifelong creative process, and not a pursuit of a single and static end-product to be preserved for all time.

Works Cited

1.Jung, C.G. “The Psychology of the Child Archetype.” The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, 2d ed., translated by R.F.C. Hull, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1968), 164.

5. Ibid., 166.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid., 170.

9. Ibid., 171.

10. Ibid., 166.

11. Ibid., 170.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

15. Ibid., 162.

16. Ibid., 164.

2. Campbell, Joseph. Romance of the Grail: The Magic and Mystery of Arthurian Myth, edited by Evans Lansing Smith, (New World Library, 2015), 155.

3. Filoni, Dave. “40 Years of Star Wars Panel | Star Wars Celebration Orlando 2017 (US).” Youtube, uploaded by Star Wars, 13 April 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YI5QodTtlME&ab_channel=StarWars

4. Jung, C.G. The Red Book: Liber Novus, 1st ed., translated by Sonu Shamdasani, (New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009), 234.

14. Tsai, Lauren. “Lauren Tsai – Fun With Dumb – Ep. 40.” Youtube, uploaded by Fun With Dumb, 30 May 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YvDFsCBDpt0&ab_channel=FunWithDumb